Editor’s Note (6/23/25): This story has been updated with additional imagery and details.

Welcome to a mind-blowing new era of astronomy.

The long-awaited Vera C. Rubin Observatory, a cutting-edge new telescope perched atop a mountain in Chile, released its first images of the universe on June 23—and its views are just as jaw-dropping as scientists hoped.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The new images come from only 10 hours of observations—an eyeblink compared with the telescope’s first real work, the groundbreaking, 10-year Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) project. On display are billowing gas clouds that are thousands of light-years away from our solar system and millions of sparkling galaxies—all emblematic of the cosmic riches that the observatory will ultimately reveal.

“You can see here a universe teeming with stars and galaxies,” said Željko Ivezić, an astronomer at the University of Washington and director of the Rubin Observatory, during a live event held by the observatory. “The seemingly empty, black pockets of space between stars in the night sky when you look at it with unaided eyes, are transformed here into these glittering tapestries.”

The Rubin Observatory released several videos to highlight the strengths of the new telescope, which captures images that are too enormous to meaningfully grasp with our perception, Ivezić explained. Each of them would require 400 high-definition televisions, a space the size of a basketball court, to display at full detail.

Among the sights that Rubin captured are individual detail images that show portions of the Virgo Cluster, a massive clump of galaxies located in the constellation of the same name (at top and below).

And the appeal of these images isn’t just aesthetic. “When I look at the images, I often don’t pay attention to the beautiful nearby galaxies; I look at the little fuzzballs,” said Aaron Roodman, a physicist at Stanford University and program lead for the Rubin Observatory’s LSST Camera, during the live event. “Many of those galaxies are five, perhaps even 10 billion light-years away and have up to 100 billion stars in them. And those are the galaxies that we use the most if we want to study the expansion of the universe and dark energy.”

Understanding dark energy—the mysterious force that propels the accelerating expansion of the universe—and the equally enigmatic dark matter, which shapes the cosmos but can’t be directly detected by scientists, represents one of the four key science pillars of the Rubin Observatory. The others include cataloging the solar system, mapping the Milky Way and exploring so-called transient phenomena that change over time.

In a small section of the Rubin Observatory’s total view of the Virgo Cluster, bright stars in the Milky Way galaxy shine in the foreground, and many distant galaxies are in the background.

NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory

The wealth of these initial views is not a matter of good luck—it’s a testament to the power of the Rubin Observatory to see the previously undetectable. “In a lot of ways, it almost doesn’t matter where we look,” Roodman said during a preview press conference held on June 9. “We could have looked anywhere and gotten fantastic images.”

In the end, the team decided to share several mosaics of images from the observatory that highlight its extremely wide field of view, which can capture multiple alluring targets in a single snapshot.

“I think the thing we hope everybody sees, also, is the promise and opportunity to find the new stuff that is just waiting for us,” said Steven Ritz, an astronomer at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and a project scientist for the Rubin Observatory, during the reveal event.

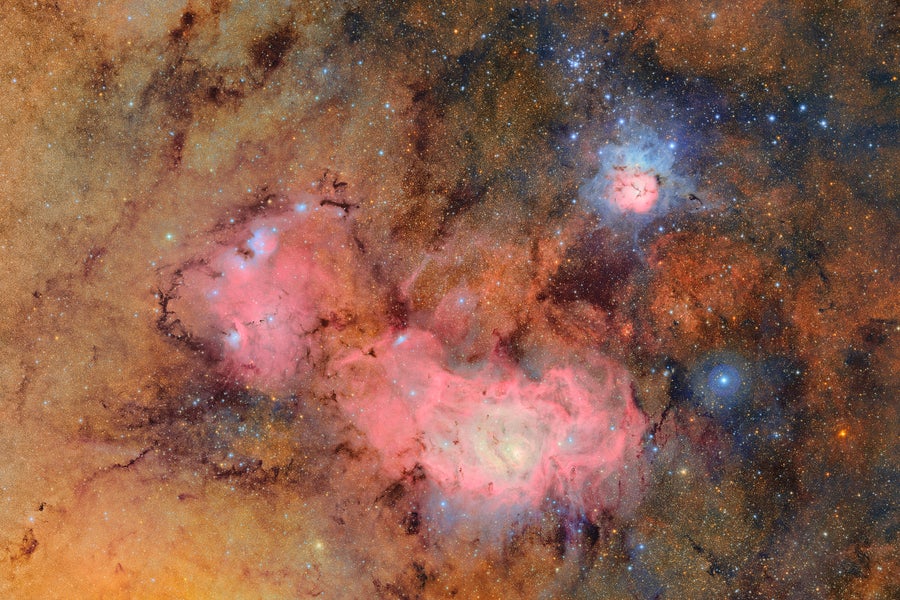

This image combines 678 separate images taken by the Rubin Observatory in just more than seven hours of observing time. Combining many images in this way clearly reveals otherwise faint or invisible details, such as the clouds of gas and dust that comprise the Trifid Nebula (top right) and the Lagoon Nebula, which are several thousands of light-years away from Earth.

NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory

The view above of the Triffid Nebula (top right) and Lagoon Nebula includes data from 678 individual images captured by the Rubin Observatory. Scientists stack and combine images in this way to see farther and fainter into the universe. The Triffid Nebula, also known as M20, and the Lagoon Nebula, also known as M8, are star-forming regions both located several thousand light-years away from Earth in the constellation Sagittarius.

The Rubin Observatory also shared a new video depicting the 2,104 asteroids the telescope has already discovered in just 10 hours of observations. The observatory expects to detect some five million asteroids that are currently unknown to scientists—compared with just one million known to date. Seven of the new asteroids are so-called near-Earth objects, although none pose a threat to our planet.

These first glimpses from Rubin showcase the observatory’s unprecedented discovery power. The telescope will survey the entire southern sky about once every three days, creating movies of the cosmos in full color and jaw-dropping detail.

A region of the sky that includes the galaxy Messier 49 and a colorful variety of other galaxies and Milky Way stars. The Rubin Observatory revealed a large number of dim objects between the brighter ones. Many of the objects have never been seen before. This view is about 1.6 times the area that Rubin captures each time it takes an image.

NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory

“We’ve been working on this for so many years now,” says Yusra AlSayyad, an astronomer at Princeton University and the Rubin Observatory’s deputy associate director for data management. “I can’t believe this moment has finally come.”