Habitual readers of this column may recall me mentioning that I have two cats. Or perhaps I should rephrase in light of the old adage “dogs have owners; cats have staff.” So let's say that two cats have deigned to live with me in return for various services I provide, such as food delivery, health care and the administration of belly rubs. I contemplate cats to the point that when I see a reference to the chemical entity known as a phorbol, I pronounce it “fur ball.”

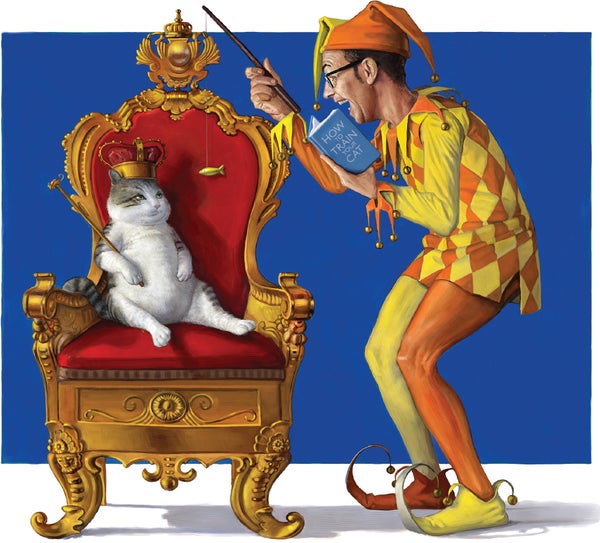

I was thus inevitably intrigued when a review copy of the new book The Trainable Cat landed (cleanly, all four corners simultaneously) on my desk. The authors are John Bradshaw, foundation director of the Anthrozoology Institute at the University of Bristol, and Sarah Ellis, holder of a doctorate in feline behavior and a specialist with the charity International Cat Care in England. The book is subtitled A Practical Guide to Making Life Happier for You and Your Cat. As intimated above, I might have gone with Making Life Happier for the Cat and Its Person, but I just work here.

Real time aside: A neighbor's cat, appropriately named Jester, has just gamboled into my home office, as he does a few times every week. “[Another cat] may even be so bold as to actually enter the house,” the Brits write. They go on to explain that “although cats learn a great deal from their owners, they can also learn from other cats … for example, how to use the cat flap.” This interloper must have observed one of the resident cats employing said cat flap (we Americans usually call it the cat door). I assumed Jester was a copycat, but the authors note, “It's not clear whether the second cat actually learns how to perform the behavior directly from the other cat or whether the more skilled cat's actions simply draw the other cat's attention to the cat flap as something worth investigating.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

If Jester (already gone) had to work out the cat door from first principles, he had plenty of time to suss out the problem. He's not binge watching dire wolves, dogs and dragons on Game of Thrones; he's not coming up with names for the orange tabby that lives atop Donald Trump's head; and he's certainly not writing a cat column on deadline.

Like an unemployed brother-in-law, Jester sometimes drops in just to see if there are any leftovers in the cat dish. “Cats are opportunists, and the chance of a free meal is something they rarely pass up,” the authors assert. Indeed, I have never seen a cat pick up a check. Although “a free meal” here probably refers to food that comes out of a can rather than by virtue of some (calorically) expensive hunting expedition.

Real time aside: One of the resident cats has just commandeered my desk chair, leaving me to finish this composition with my derriere planted on a milk crate. Which leads to the first lines of the book's introduction: “Who on earth trains cats?” (Not me, obviously. In fact, I've been trained by them—I'm sitting on a milk crate.)

The authors then mention that big cats and domestics have been trained for performing, but “why would anyone want to train their pet cat, except perhaps to show off their feline accomplice's talents to their friends?” In truth, your friends will be less enthralled than you'd think by an exhibition of your cat chasing a laser light through the living room.

No, the book's serious purpose is “to show you how training can improve not just your relationship with your cat but also your beloved pet's sense of well-being.” As I look at the cat sleeping contentedly in my chair, I wonder how its sense of well-being could possibly enlarge. Fortunately, I now have possession of an owner's—make that user's—manual.