Cuttlefish wave their expressive tentacles in four distinctive dancelike motions, a new study finds—possibly to communicate visually and by vibration.

These marine invertebrates, which have eight sucker-lined “arms” and two additional tentacles near their mouth, have been known to alter their body’s color pattern to blend in with the background or create zebralike stripes to attract a mate. Some have been known to raise their arms to intimidate predators, and others to extend a particular arm to signal a mating desire.

But cognitive neuroscientist Sophie Cohen-Bodénès and computational modeler Peter Neri, both then at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, noticed cuttlefish doing something that hadn’t been described before: making specific, repeated and relatively complex arm gestures at one another.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

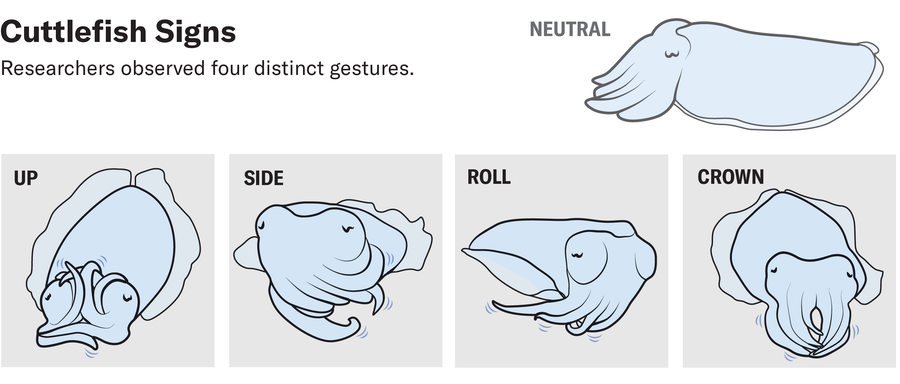

Studying two species, common cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) and dwarf cuttlefish (Sepia bandensis), the two researchers have identified four arm-waving signs, which they call “up,” “side,” “roll” and “crown.” The scientists recently posted their observations on the preprint server bioRxiv.

The four cuttlefish gestures: “up,” “side,” “roll” and “crown.”

Cohen, Sophie (2025), “Cuttlefish interact with multimodal arm wave sign displays”, Mendeley Data, V4, doi: 10.17632/f3sp55762b.4, CC BY 4.0

The “up” sign involves a cuttlefish extending one pair of arms upward as if swim dancing to the Bee Gees song “Stayin’ Alive” while twisting its other arms together in the middle. For the “side” sign, the animal brings all its arms to one side of its body or the other. A cuttlefish makes the “roll” sign by folding all its arms underneath its head as if it is about to do a front flip (which makes its eyes bulge out). And the “crown” sign is rather like when a person puts the fingertips of both of their hands together to form a pyramid shape.

Cohen-Bodénès and Neri recorded cuttlefish signing in various contexts and played the videos back to different cuttlefish. “We found that when they see [others] signing, the cuttlefish sign back,” Cohen-Bodénès says. “We don’t think it’s a mimicking signal because when they sign back, they sometimes display different types of signs.” This behavior suggests a possible communication process, Neri adds.

The researchers also used a hydrophone—a device used to record sounds underwater—to capture the vibrations each sign created. They then played those vibrations back to cuttlefish that couldn’t see the signs but could feel the changing pressure in the surrounding water—and the cuttlefish still responded with their own signs. This finding is the first piece of evidence that cuttlefish might communicate with one another by emitting specific vibrational signals, Cohen-Bodénès says. Cuttlefish may detect these signals with saclike sense organs called statocysts or with an array of sensory cells running along their skin, similar to the lateral line system used by fish.

Amanda Montañez; Source: “Cuttlefish Interact with Multimodal 'Arm Wave Sign' Displays,” by Sophie Cohen-Bodénès and Peter Neri in BioRxiv. Published online May 5, 2025 (reference)

The researchers “have found some fascinating behaviors,” says Willa Lane, a marine biologist and psychologist at the University of Cambridge, who says she has seen the crown behavior in cuttlefish in her laboratory. She finds it particularly compelling that the arm movements were observed in two species.

Because the species Cohen-Bodénès and Neri studied don’t overlap in their geographic ranges and cuttlefish are quite solitary, Lane wonders whether the signals might be used to confuse prey during hunting or to scare off predators—or even as part of interactive hunting with other species, a behavior that has been observed in octopuses.

“It’s interesting that they communicate visually and maybe acoustically,” says Sam Reiter, a neuroethologist at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology in Japan. He and Neri agree that before this behavior can technically be called a “sign language,” researchers must show the signals’ distinct meanings in particular contexts.

Still, the signals do add to the evidence of how smart cuttlefish are. “In terms of intelligence, they are, in my view, very much comparable to octopuses,” Cohen-Bodénès says.