Sam’s father sat slumped on the leather couch in the clinical interview room, head in his hands. He had just finished telling the long, painstaking history of his son’s descent into psychosis. Sam (whose name has been changed to protect his confidentiality), then 17, had started casually using marijuana with friends in the ninth grade. He “dabbled” with other substances as well (Xanax, Ecstasy), but he used cannabis most consistently.

Sam’s father told me that he and his wife had used cannabis themselves a fair amount in college and were inclined to agree with their son when he told them, “Don’t worry, it’s just pot!” They pleaded with him to buy it from cannabis shops rather than getting it “on the street.”

In California, where I work as a researcher and clinician studying the links between cannabis use and psychosis, it is not difficult to get a medical marijuana card, even for a teenager.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Sam started high school as a fairly good student with several friends. Over time he began using cannabis daily. He took it a variety of ways, first with friends at parties and then, more and more often, alone. His parents noticed increasingly odd behavior: He blocked the camera on his laptop and placed cardboard over the windows in his room. He stopped showering. He began refusing to go to school. Against Sam’s will, his parents took him to a rehab facility for teens. During the three-week program he was fully abstinent from cannabis, but, disturbingly, his psychotic symptoms got worse rather than better; simply stopping wasn’t enough for Sam to recover.

By the time his family came to my clinic, he had had persistent delusions for more than six months. Sam was fully convinced that the government was following him and constantly surveilling him. Although we don’t know whether cannabis caused Sam’s psychosis, it was striking that his symptoms didn’t go away when he stopped using. It is possible cannabis had altered his brain function.

Modern-day cannabis is simply not the same as the plant used in the 1960s through the 1980s or even as recently as 10 years ago. New strains of cannabis are highly potent, making them more addictive and potentially more dangerous, and we are still trying to understand what the drug does to developing adolescent brains. As a scientist and a parent, I recommend that people avoid using cannabis until at least their mid-20s, but I realize this advice may not be realistic. If your teens are going to use today’s cannabis, it is critically important that you be aware of the data showing what a different beast this substance has become and the risk of major mental health issues it poses.

All cannabis products contain a mix of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the intoxicating component of the cannabis plant, and cannabidiol (CBD), which may have anxiety-reducing properties. In the 1990s the marijuana in a typical joint contained about 5 percent THC.

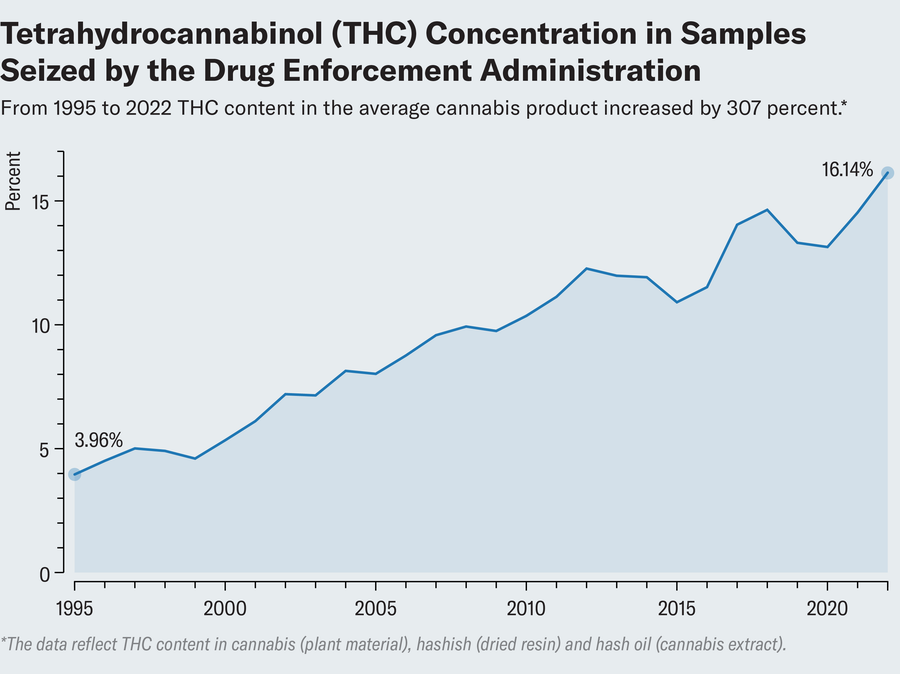

But genetic modification has drastically increased THC potency; from 1995 to 2022 its content in the average cannabis plant increased by 307 percent. And it’s not just joints or pot brownies; with the expanding legalization and commercialization of cannabis, there are few limits on the levels of THC in products such as fast-acting vape pens and edibles. What Sam and other teens can buy today is nothing like what their parents used in college.

Ripley Cleghorn; Source: Cannabis Potency Data, National Institute on Drug Abuse

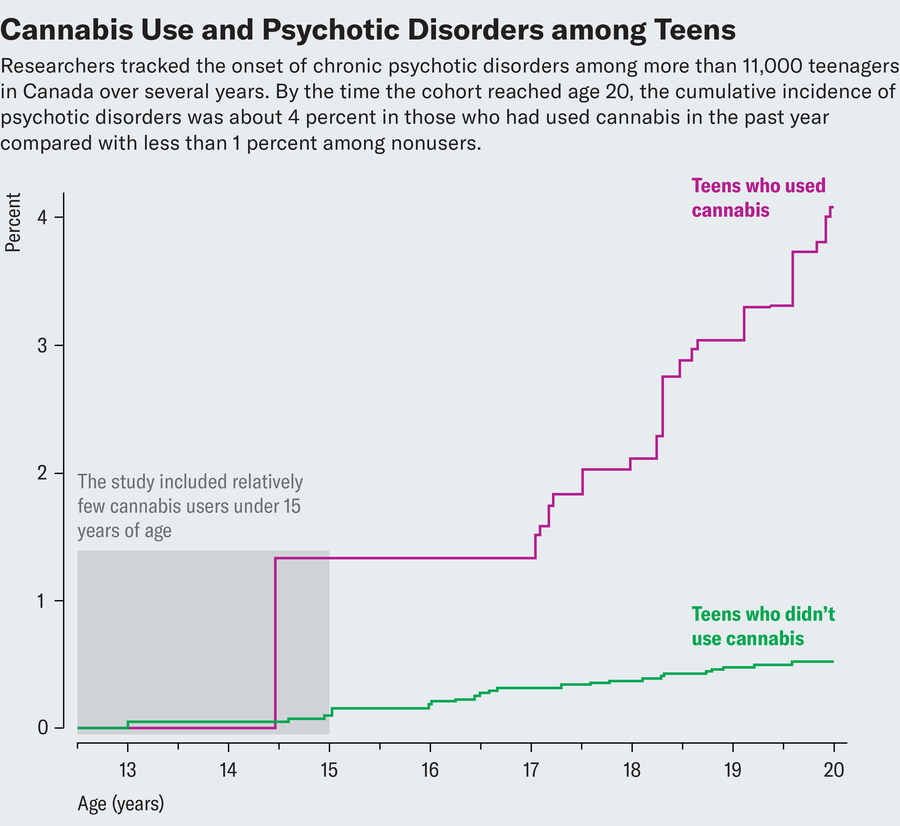

Higher-potency THC, marijuana use starting at a young age and more frequent use all increase the risk of psychosis. A Canadian research team studying more than 11,000 teens found that compared with nonusers, cannabis users faced an 11-fold increase in the risk of developing a psychotic disorder. In light of such daunting data, some researchers have begun sounding the alarm. But we are struggling to get this information to those who need to hear it most: parents, educators and legislators. And although there isn’t a clear consensus that cannabis causes psychosis, studies like the ones I’ve mentioned, which are well designed and carefully analyzed, indicate that the two things are associated.

André J. McDonald, modified and restyled by Ripley Cleghorn; Source: “Age-Dependent Association of Cannabis Use with Risk of Psychotic Disorder,” in Psychological Medicine, Vol. 54, No. 11; August 2024

Another big question we are trying to answer: Why is the increased risk of psychosis so profound in teens? The researchers in my field think it has something to do with the significant rewiring that happens in adolescent brains, which continues into our early 20s, when symptoms of psychotic disorders typically start showing up. The same molecules and receptors in our brains that interact with THC (known as the endocannabinoid system) play an essential role in brain development. And there is growing evidence from both animal and human studies that early cannabis exposure can disrupt the way brain cells, or neurons, respond to what we experience and how they communicate with one another to make those experiences memories.

So how do you talk to your kids about cannabis? When families come to my clinic for youth at risk for psychosis, my colleagues and I ask the kids why they use cannabis and how they feel afterward. We ask them why they might stop using and whether they could stop if they needed to. And then: Why not try stopping for a few days and see how you feel? The answers help us assess whether the person has a cannabis addiction.

Some teens tell us they can stop. But others aren’t willing. For them, we recommend that they avoid high-potency products and instead choose products with higher CBD-to-THC ratios.

If you have a teenager at home or will soon, the odds are that they are going to be exposed to a lot of cannabis in many forms—at school, at parties, all around the neighborhood. It is never too early to have that conversation. To get ready for it, make sure you have good “cannabis literacy.” The National Institute on Drug Abuse is a good place to start. Encourage your child to seek out reputable sources of information, too, rather than believing what they hear from friends or see on social media. It can be helpful to set clear rules and boundaries around cannabis use that you all agree on and establish what the consequences are for breaking those rules. Parents should foster clear, nonjudgmental communication about use and assure their children that it’s okay for them to share their questions and concerns.

For Sam, we recommended ongoing psychiatric treatment and family therapy, which his parents found valuable given that their son was living with a chronic psychotic disorder. If your child starts experiencing worrisome symptoms or engaging in unusual behaviors—such as isolating themselves from others, talking to themselves, or hearing or seeing things that other people don’t—seek psychological treatment right away. Your family physician or child’s pediatrician can provide a referral to a specialist for an evaluation and treatment.

Like so many things our children are exposed to now, the vastly changed landscape of cannabis products and their availability is an experiment none of us consented to in an informed way. The best we can do is try to make our retroactive consent (and that of our kids) as informed as possible.