Researchers once thought of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as an unchanging condition: either you have it or you don’t, end of story. But it’s become clear that ADHD symptoms can change across a person’s lifespan, and now research shows that symptoms can even shift over the course of a menstrual cycle.

The new findings, which were presented at the U.S. Psychiatric and Mental Health Congress but have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal, provide the strongest evidence so far that ADHD symptoms can fluctuate along with hormonal shifts.

“It gives us a personalized insight into what is happening for many women with ADHD,” says Dora Wynchank, a psychiatrist and researcher at Dutch mental-health-care organization PsyQ, who was not involved in the study. “Because ADHD historically has been studied in boys and men, we’ve missed out on this very important aspect.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Michelle Martel, a clinical psychologist and chair of the psychology department at the University of Kentucky, led the research, which followed 97 female college students across their menstrual cycle. Nearly all participants had a formal ADHD diagnosis, and roughly half took psychostimulants for treatment. Martel’s team measured participants’ hormone levels every day and assessed their ADHD symptoms with questionnaires and cognitive tests.

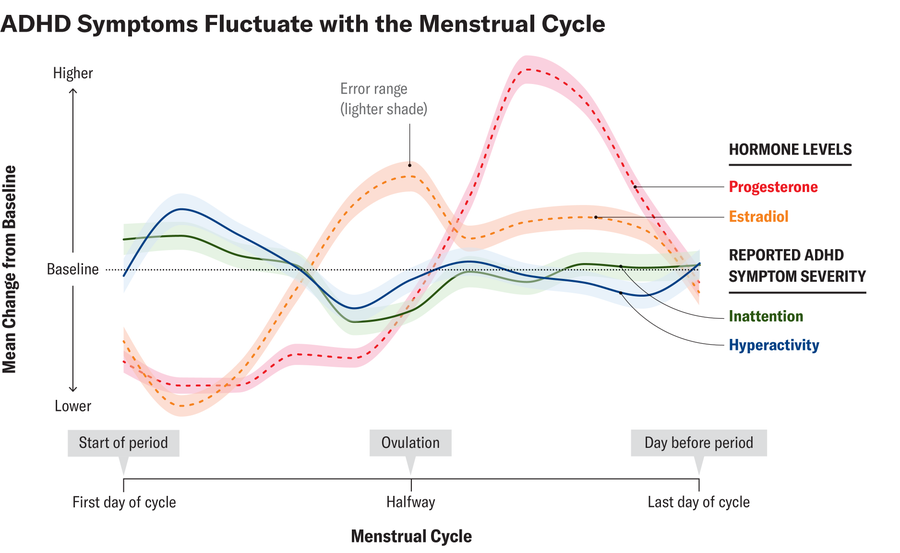

Martel and her colleagues found that participants reported worse ADHD symptoms, such as inattention and impulsivity, just before and at the start of their period and, to a lesser extent, around ovulation. This aligned with the results of cognitive tasks, and it also echoes what many psychologists, including Martel and Wynchank, have already heard from their patients.

Ripley Cleghorn; Source: ADHD in Adult Women: Challenges and New Directions,” by Michelle M. Martel. Presented at Psych Congress, Boston, November 2024 (data)

Wynchank says clients have told her that “something happens to me in the week before my period when all hell breaks loose. A couple days into my period, I look back, and I don’t recognize myself. And this comes back every month.”

Martel says these changes appear to be largely caused by drops in estradiol, the most powerful form of estrogen. Estrogen is mostly known as a sex hormone, but it’s also active in the brain, aiding in attention, memory and mood stabilization. Plus, it helps the body produce and maintain levels of dopamine, an important brain-signaling chemical that plays a central role in ADHD.

“It’s about a sensitivity to hormonal fluctuations,” Wynchank hypothesizes. “That combination of poorly operating dopamine and low levels of estrogen is just a sort of double whammy that makes the cognitive symptoms so much worse.” This interaction might explain why studies show higher rates of premenstrual dysphoric disorder—a severe form of premenstrual syndrome—in people with ADHD, as well as a higher likelihood of postpartum depression and worsened perimenopause symptoms. Estrogen levels are known to drop before menstruation, after a person gives birth and around menopause.

Martel’s newest results show the same effect seen in her 2018 preliminary study of 32 participants. “It’s really just verifying everything we found before,” Martel says. “It really does allow us to trust that these results are accurate, that we’re picking up on something real.”

The findings could redirect the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD. In Martel’s preliminary study, some participants met the criteria for ADHD only at certain points in their menstrual cycle, which could affect their ability to be diagnosed. And Martel wants to explore whether some people would benefit from cyclical adjustment to their ADHD medication.

Wynchank and her collaborators published a case study in 2023 that supports this idea of a cycle-specific prescription. The researchers prescribed an increased premenstrual dose of ADHD medication to nine of their patients and followed them for six months to two years. All participants reported improved symptoms without increased side effects and planned to continue the titrated dose. Wynchank notes that other measures, such as psychotherapy and hormonal birth control, may help with worsened premenstrual ADHD symptoms, but they haven’t yet been studied in depth.

Both Wynchank and Martel agree that a lot of work remains to be done in this area. “ADHD is definitely dramatically understudied in girls and women,” Martel says. To combat this disparity, Wynchank and her collaborators are currently conducting a worldwide survey of women with ADHD. “We want to know what the lived experience is for women with ADHD and what their research priorities are,” Wynchank says. “It’s not about what we’re interested in researching. We want that to come from the women themselves.”