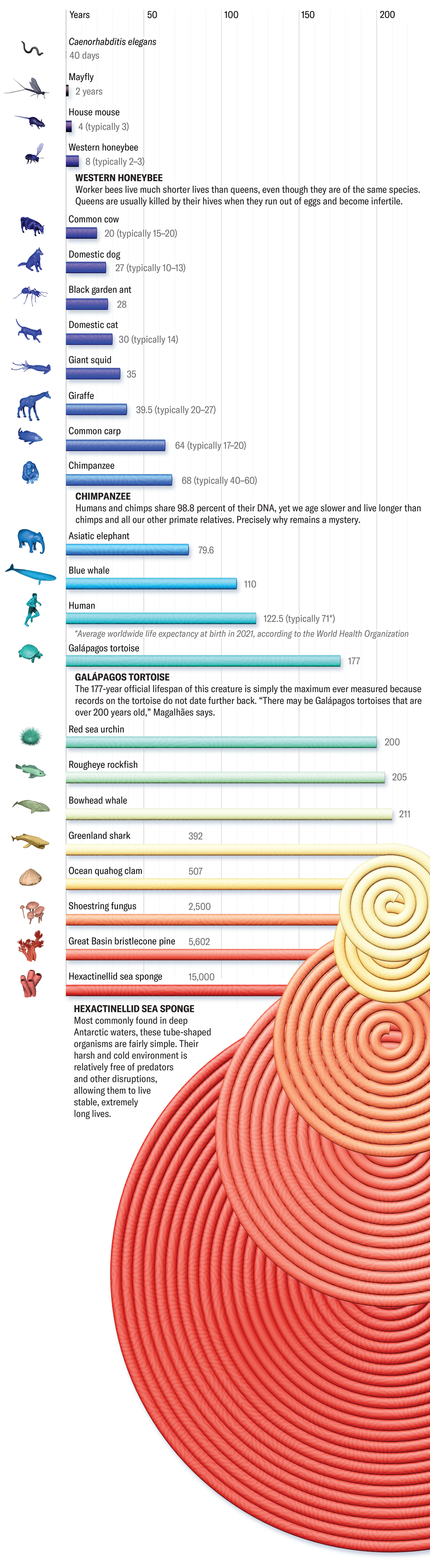

Some species seem to live fast and die young. Others, though, “appear not to age,” says João Pedro de Magalhães, a molecular biologist at the University of Birmingham in England. He is project leader of the Human Ageing Genomic Resources program, which keeps the AnAge database of maximum animal lifespans. Some species of turtles, fishes and salamanders, for instance, don’t show any signs of degeneration or senescence as they grow older. If they didn’t die of predation, accidents or infectious disease, they could live extremely long lives, Magalhães says.

“It’s a biological mystery why some species age faster than others,” Magalhães says. “We still don’t understand well the mechanisms behind aging.” Species that face high predation usually evolve to grow quickly and reach sexual maturity rapidly. Other creatures that don’t face pressure to reproduce early can age slowly: Greenland sharks, for instance (the top of their food chain), may take 150 years to reach sexual maturity.

DNA mutations are thought to play a role in determining lifespans, with longer-lived species tending to evolve better DNA-repair systems to help ward off cancer. Short-lived creatures, such as mice, don’t have these abilities, because in the wild they often die of predation before cancer becomes an issue. Laboratory-raised mice, however, have very high rates of cancer.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

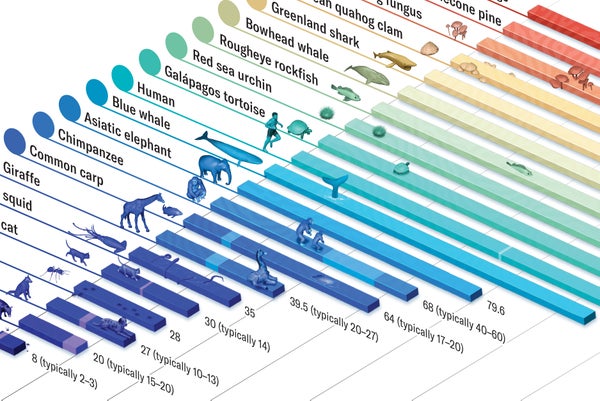

Mark Belan; Source: AnAge: The Animal Ageing and Longevity Database/Human Aging Genomic Resources (longevity data); Animal Diversity Web (most of the typical lifespan values)